So here I am at the end of my holiday, staring into the yawning abyss of the rest of the year working. It's been a good break, I've taken a little trip to the sea, I've designed my book which is now being printed, I've played a lot of guitar through my self-present - a 7 watt Cornell Plexi, I've organised my financial paperwork (yawn) and I've seen friends and relaxed a good deal (yay).

The week has finished in quite an architectural fashion. On Thursday I finally made it to the

Sir John Soane Museum which is a five minute walk from Schossadlerflug but has erratic opening hours meaning that is has taken until now for me to be in the area with time to go and see it. The museum is in fact Sir John's house in which he stored his collection of architectural treasures. One of the pre-eminent neo-classical architects of his day, Sir John, having fallen out with his one surviving son, got an act of Parliament passed which legislated that upon his death the house and all its contents were to be left to the nation in perpetuity provided that the collection and the building were maintained exactly has he left them. In 1837 Sir John Soane died and the building has been free to visit ever since.

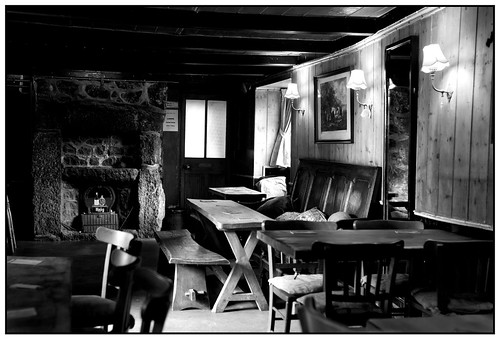

It's a remarkable space, partially because of the breadth of his collection but mostly to see a Regency house intact with all its correct detailing, paintwork and so on. In in a more normal museum the focus is just on the artifacts, in Sir John's house the building itself and the way he chose to display his collection are just as important as the pieces themselves. Amongst the delights are the picture room which contains many Hogarths, some displayed on large panels which hinge out from the wall because he had too many pictures to get them all on the walls at once. Downstairs there is the Monk's parlour, a secluded room with low light, black painted furniture including a table with a carved stone human skull in its centre. Returning to the ground floor there is the the Museum Corridor, a long room, two stories high, packed from floor to ceiling with casts of architectural details from antiquity along with the usual busts of Homer and the like which were so popular at the time. It is hard to describe the effect of being in a space like this. Although there are many buildings in London which pre-date the 1830s by hundreds of years there are very few that are preserved as the once were. It is the nature of London to take its existing structures and adapt them, modify and remodel them over the years until the steady accretion of detail turns them into something that would not be easily recognised by the original architect or occupant. Sir John Soane's museum allows the visitor, just briefly, to travel a little in time and offers us a glimpse into the life of a fascinating man, almost as if he were with us whilst we did it.

By contrast on Saturday I went to the Design Museum just beyond Tower Bridge. The reason for my visit was an exhibition of the work of Richard Rogers, the architect of the Lloyd's building in London and the Centre Pompidou in Paris most famously. Lord Rogers has long advocated more sensible city planning with a view to consuming fewer resources and making cities more self-sufficient in energy. The most interesting parts of the exhibition for me were the smaller projects of environmentally focused modular housing designs, some of which are

now being constructed. The houses are made of pre-fabricated sections of sustainable materials and take only 24 hours to assemble into a functional house. The modularity of the design allows the house to be extended to contracted as the needs of the occupants change over time. It is efficient in its use of heating and water and has innovations such as larger, taller windows to allow more light in for longer periods of the day thus reducing the length of time that light bulbs are required. There were similarly inspired tower block designs for cities, one of which is about to built as part of the redevelopment of the Elephant and Castle are of South London, near where I used to live.

It was interesting to compare a leading light of regency architecture with a modern master of the form and to compare how differently they appear to see building, what concerns they had about their designs and what functions their buildings needed to serve. The only real point of similarity I could see was that they both produce buildings that, with hindsight, seem so utterly emblematic of the times of their construction - The Bank of England or Dulwich Picture Gallery seem so early nineteenth century with their monumental updating of classical themes whilst the Lloyd's Building is so evocative of the 1980s obsession with new technology, materials and display of power and wealth. A very interesting contrast.